Wednesday, May 15, 2013

Feds seize money from Dwolla account belonging to top Bitcoin exchange Mt. Gox

The Department of Homeland Security has apparently shut down a key mobile payments account associated with Mt. Gox, the largest Bitcoin exchange.

Chris Coyne, the co-founder of online dating service OKCupid, tweeted out an e-mail he received from Dwolla this afternoon. The e-mail states that neither Coyne, nor presumably any other Dwolla user, will be able to transfer funds to Mt. Gox.

Dwolla confirmed the change to the New York Observer, which first reported the story. Dwolla received a seizure warrant from a federal court.

"The Department of Homeland Security and US District Court for the District of Maryland issued a ‘Seizure Warrant’ for the funds associated with Mutum Sigillum’s Dwolla account (a.k.a. Mt. Gox)," a Dwolla spokesperson told NYO's BetaBeat. "Dwolla has ceased all account activities... for Mutum Sigillum while Dwolla’s holding partner transferred Mutum Sigillum’s balance, per the warrant."

It isn't yet clear why this seizure happened, and Dwolla isn't saying anything beyond confirming the court order. Mt. Gox didn't immediately responded to an inquiry from Ars about the seizure. A user on Bitcoin StackExchange published this short reply received from an inquiry to Mt. Gox about the shut-down: "Thank you for the e-mail. We can see that the Dwolla transactions are not getting processed right now. We will contact Dwolla and post an announcement regarding this. Your patience is appreciated till then."

A DHS spokeswoman declined to comment on the case, "in order not to compromise this ongoing investigation being conducted by ICE Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) Baltimore."

Using a payment service like Dwolla is one of the easiest ways for US residents to buy Bitcoins. More popular payments services can't be used to buy on the Mt. Gox exchange—PayPal, for instance, can't be used to perform currency exchanges. Mt. Gox is the largest Bitcoin exchange, handling about 63 percent of all Bitcoin purchases.

Someone Else Owns Your Genes

How it happened, why it matters now, and why it won’t be a big deal in the future.

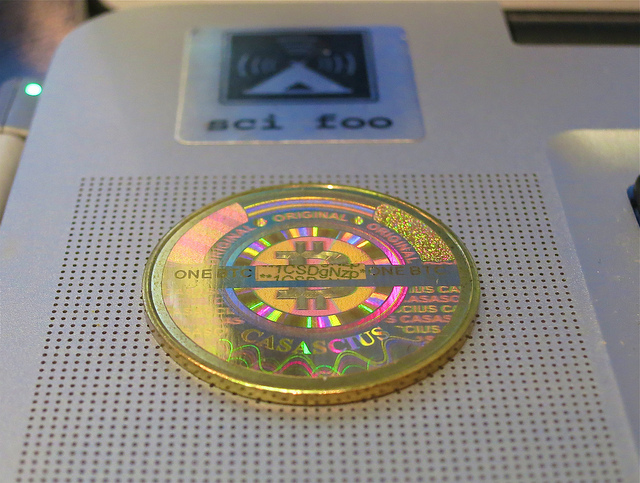

(PHOTO: ABODE OF CHAOS/FLICKR)

May 14, 2013 • By Michael White • Leave a Comment

772 Flares

772 Flares

×

(PHOTO: ABODE OF CHAOS/FLICKR)

May 14, 2013 • By Michael White • Leave a Comment

772 Flares

772 Flares

×

On April 15, in the case of The Association for Molecular Pathology vs. Myriad Genetics, Inc., the United States Supreme Court heard arguments questioning the legitimacy of patents on human genes. A genetic testing company, Myriad Genetics, has patent claims on two human genes that influence a person’s risk for breast cancer. Myriad is being sued by a conglomerate of physicians, scientists, and patients who argue that Myriad has illegitimately patented a product of nature. While the lawyers and Justices delved into the arcana of patent law and molecular biology, many of the rest of us were wondering: how the heck can you patent someone’s genes?

The idea of having your genome Balkanized into small fiefdoms of intellectual property may sound offensive, but do gene patents make any practical difference?

Well, genetic information, much like a text, is encoded as a sequence of chemical “letters.” The alphabet of DNA consists of four letters (whose chemical names are abbreviated as A, C, T, or G), and each gene is made up of a sequence of tens of thousands of these letters. Scientists read the text of a gene by “sequencing” it: determining its sequence of letters. Knowing the sequence of a gene is not just important to scientists who study how that gene works; the sequence is also important for patients who are worried about their genetic risk for certain diseases. Each of us has small misspellings, deletions, and insertions scattered all over our genetic text—it’s what makes us unique from one another—and while most of these mutations are harmless, some are dangerous. For example, the information in the sequence of your particular copy of the gene BRCA1 can tell you whether you are at high risk for breast cancer. By sequencing the BRCA1 gene, you (or your mother, wife, or daughter) can find out whether you have a high-risk version of BRCA1—as long as you pay Myriad Genetics to read your sequence, because Myriad owns a patent on the sequence of your BRCA1 gene.

How did Myriad Genetics get a patent on the naturally occurring DNA sequence of the BRCA1 gene of every man, woman, and child in America? (They also own a patent on the sequence of BRCA2, another breast cancer risk gene.) Here’s the trick: you can own the naturally occurring sequence of a gene by making a patent claim to all physical copies of that sequence that exist outside of human cells.

This trick works because, in the process of sequencing a gene, scientists create a synthetic copy. This synthetic copy is chemically the same as the original; it has the exact same sequence of chemical letters that was put together by nature inside your cells. Synthetic copies of genes are routinely created in the lab using very general methods widely used by molecular biologists for decades, methods that were not invented by Myriad Genetics. However, Myriad was first to sequence the BRCA1 gene, and they claimed physical copies of the BRCA1 sequence as their original invention. The result is that nobody can read the sequence of any BRCA1 gene of anyone in America without Myriad’s permission.

THE IDEA OF HAVING your genome Balkanized into small fiefdoms of intellectual property may sound offensive, but do gene patents make any practical difference? Yes and no. If you are worried about your genetic risk for breast cancer and Myriad doesn’t take your insurance, you’re out of luck. Want a second opinion on Myriad’s interpretation of your genetic risk? Nobody is legally allowed to offer one. Aggressively protected gene patents also interfere with basic research focused on studying how genes function and contribute to disease, because they prevent scientists from using basic research tools to study those genes.

(What’s the point of a gene patent, then? Money. Your BRCA1 sequence is important to you, and Myriad wants you to pay them, and only them, for it.)

On the other hand, the era of human gene patents appears to be ending, regardless of what the Supreme Court decides. Myriad Genetics obtained its gene patents at a time when sequencing one gene was a big job; with the same effort today, we can sequence thousands of genes at once. A company that offers to predict your genetic risk for disease by reading only a single gene is going to look shabby compared to competitors that offer to sequence a large fraction of your genome to give you a much more comprehensive estimate of your genetic risk. Gene patents may hold off the competition for a limited time (while also temporarily holding up some basic genetics research and causing anxiety and suffering among patients), but they won’t stop the arrival of a new standard of genetic testing based on low-cost readings of all your genes.

New App Lets You Boycott Koch Brothers, Monsanto And More By Scanning Your Shopping Cart

In her keynote speech at last year’s annual Netroots Nation gathering, Darcy Burner pitched a seemingly simple idea to the thousands of bloggers and web developers in the audience. The former Microsoft Microsoft programmer and congressional candidate proposed a smartphone app allowing shoppers to swipe barcodes to check whether conservative billionaire industrialists Charles and David Koch were behind a product on the shelves.

Burner figured the average supermarket shopper had no idea that buying Brawny paper towels, Angel Soft toilet paper or Dixie cups meant contributing cash to Koch Industries Koch Industries through its subsidiary Georgia-Pacific. Similarly, purchasing a pair of yoga pants containing Lycra or a Stainmaster carpet meant indirectly handing the Kochs your money (Koch Industries bought Invista, the world’s largest fiber and textiles company, in 2004 from DuPont).

At the time, Burner created a mock interface for her app, but that’s as far as she got. She was waiting to find the right team to build out the back end, which could be complicated given often murky corporate ownership structures.

She wasn’t aware that as she delivered her Netroots speech, a group of developers was hard at work on Buycott, an even more sophisticated version of the app she proposed.

“I remember reading Forbes’ story on the proposed app to help boycott Koch Industries and wishing that we were ready to launch our product,” said Buycott’s marketing director Maceo Martinez.

The app itself is the work of one Los Angeles-based 26-year-old freelance programmer, Ivan Pardo, who has devoted the last 16 months to Buycott. “It’s been completely bootstrapped up to this point,” he said. Martinez and another friend have pitched in to promote the app.

Pardo’s handiwork is available for download on iPhone or Android, making its debut in iTunes and Google Google Play in early May. You can scan the barcode on any product and the free app will trace its ownership all the way to its top corporate parent company, including conglomerates like Koch Industries.

Once you’ve scanned an item, Buycott will show you its corporate family tree on your phone screen. Scan a box of Splenda sweetener, for instance, and you’ll see its parent, McNeil Nutritionals, is a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson Johnson & Johnson.

Even more impressively, you can join user-created campaigns to boycott business practices that violate your principles rather than single companies. One of these campaigns, Demand GMO Labeling, will scan your box of cereal and tell you if it was made by one of the 36 corporations that donated more than $150,000 to oppose the mandatory labeling of genetically modified food.

Deciding to add that campaign to your Buycott app might make buying your breakfast nearly impossible, as that list includes not just headline grabbers like agricultural giant Monsanto but just about every big consumer company with a presence in the supermarket aisle: Coca-Cola, Nestle, Kraft, Heinz, Kellogg’s, Unilever and more.

Buycott is still working on adding new data to its back end and fine-tuning its information on corporate ownership structures. Most companies in the current database actually own more brands than Buycott has on record. The developers are asking shoppers to help improve their technology by inputting names of products they scan that the app doesn’t already recognize.

And if this all sounds worthy but depressing, be assured that your next trip to the supermarket needn’t be all doom and gloom. There are Buycott campaigns encouraging shoppers to support brands that have, say, openly backed LGBT rights. You can scan a bottle of Absolut vodka or a bag of Starbucks coffee beans and learn that both companies have come out for equal marriage.

“I don’t want to push any single point of view with the app,” said Pardo. “For me, it was critical to allow users to create campaigns because I don’t think its Buycott’s role to tell people what to buy. We simply want to provide a platform that empowers consumers to make well-informed purchasing decisions.”

Forbes reached out to Koch Industries and Monsanto for comment and will update this story with any responses.

Update: Tuesday’s traffic surge is causing some problems for Buycott. Pardo says he’s working to fix issues with the Android app in particular. “The workload is a bit overwhelming now,” he said. “For example, our Android app was just recently released and the surge of new users today has highlighted a serious bug on certain devices that needs to be fixed immediately. So all other development tasks I was working on get put on hold until I can get this bug fixed.”